Jessica Hubert just returned from participating at the 2025 Accessibility Professionals Association conference in Austin, Texas. In this post, Jessica shares her personal insights into the role of fire protection professionals in providing accessibility for people with disabilities.

It is an enlightening read.

Jessica Hubert at APA Conference 2025

Introduction

Before accessibility for people with disabilities was officially addressed by the federal government in the US in 1973, it was in the hands of our fire protection industry and safety codes. Fire protection engineers began with the need to create accessibility for people with disabilities when considering life safety and egress. In school, we learned how to account for people with disabilities with turning radii minimums, minimum door widths, minimum hallway widths, and differing egress speeds and challenges. It is still in our hands to accommodate, design, and enforce more effective and stringent accessibility requirements as we learn more and gather more data.

Personal Experience

I started as a fire protection engineering student at the University of Maryland in August 2002. That timing means that we studied the fires, egress, and collapse of the World Trade Center building on 9/11/2001 for four years. I watched desperate people jumping out of a high rise repeatedly for four solid years. We felt and studied the crowd crush nightmare of the Station Nightclub Fire in 2003, and the egress failure of the Cook County Building in Chicago in 2006. Since the dawn of our industry, these tragedies and incidents drive change and show us how we can improve upon our shortcomings. The lives lost are the reason many of us keep learning and pushing for the best life safety in the built environment that we can achieve.

Accessibility Insights

As an undergraduate, I also had the opportunity to dive deeper into the world of accessibility for people with disabilities while doing safety and access inspections of Capitol Hill as an intern for the Federal Office of Compliance. I had learned about accessible means of egress, barrier removals, reach ranges, visual alarms, protruding objects, and all the other requirements noted in standards and codes. With the inspections, I was seeing it in action. I was understanding what a true barrier a steep ramp or heavy door was to a mother pushing a wheelchair for her teenager. The importance of this work has never escaped me. However, where we were and are on the path toward universal accessibility had escaped me. Like many of us in fire protection, I believed that accessibility was handled by the codes and standards. We had addressed it. We did a good job. The job was done, and there was no need to rock the boat. Yet, there was one thing that had always bothered me since the first day I learned about it in class. We all know not to use the elevator in case of a fire. Fire protection engineers know there is a protected space near elevator lobbies or stairwell entrances called an “area of refuge,” where people who cannot use the stairs can wait for help. I could never forget the thought of what it must be like to sit still in an emergency and wait for help, knowing that you cannot help yourself. I could never forget that people with disabilities never had a chance to survive 9/11/2001, the Station Nightclub Fire, and all the other deadly incidents in our history.

Since becoming a wheelchair user in 2013, I have dedicated countless hours and spent my income volunteering and advocating for accessibility for people with disabilities in the fire codes. It began when I was invited to be a member of the Disability Access Review Advisory Committee (DARAC) for the NFPA. Each year has been very productive, and each year we add new voices and data to the conversation. We keep moving the needle slightly. Since the first day in ICU as a person with a disability, the “area of refuge” has personally haunted me. Knowing exactly where I do not stand is not a comfortable place to be in. Yet, change never occurs from a place of comfort.

A Turning Point

Figure 1 From the left: Dan Buuck, NAHB; Gene Boecker, CCI; Jessica Hubert, GSI; Joseph Wages, NEMA

This year, I have decided to make it official. In 2024, I became a member of the Accessibility Professionals Association (APA) when I was asked to revisit a presentation from the 2024 NFPA Conference and Exposition for their annual conference. The speakers we heard from over 3 days all gave useful and thorough information to a continuously rapt, invested, and engaged audience. We had the opportunity to hear from John Wodatch, the disability rights attorney responsible for authoring and implementing section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, authored the US government’s disability rights regulations, and created and led the Department of Justice’s office in charge of enforcing the ADA. Although she was unable to make this conference, my vice chair and mentor at DARAC, Marsha Mazz, also led the development of the accessibility guidelines under the ADA and the Architectural Barriers Act. She inspires me daily and has for 11 years. My ability to be an active member of society, work, get medical care, go to sporting and entertainment events, use public transportation, use sidewalks, fly on a plane, take my child to the park, drive, and grocery shop are all because of these people’s altruistic spirits and careers.

Figure 2 APA National Conference Banner. More info on the speakers and presentations can be found at https://accessibilityprofessionals.org

Sprinkler Standpipes as Protruding Objects

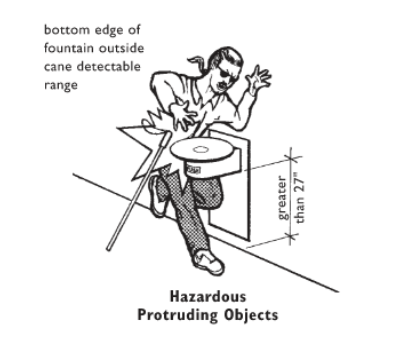

A problem of particular interest to our fire protection community was brought to my attention repeatedly throughout the course of the conference. Under the Fire Protection umbrella we are responsible for applying and enforcing accessibility for people with disabilities requirements through our fire codes standards, guidelines and designs. However, one problem comes up repeatedly in inspections. Sprinkler standpipes, hose reels and fire department connections are being installed and mounted in stairwells in ways that create protruding object barriers to people with visual disabilities. A summary of the guidelines for protruding objects is given below.

| Figure 3 Hazardous Protruding Objects for blind people, courtesy of Gene Boecker |

Access Guidelines for Protruding Objects

-

- NFPA 5000, Building Construction and Safety Code, 2024 edition, Section 12.4 Protruding Objects, mandates that protruding objects within circulation paths comply with ICC/ANSI A117.1 Accessible and Usable Buildings and Facilities, Section 307. ICC / ANSI A117.1

-

- Requirements for protruding objects apply to all circulation paths within rooms and spaces off corridors, interior and exterior circulation paths, stairways and their landings.

-

- Objects with leading edges > 27 inches (0.68 m) and < 80 inches (2.03 m) in height above the finished floor cannot protrude more than 4 inches (101 mm) into a circulation path.

-

- Objects mounted on posts cannot protrude more than 12 inches (0.304 m) from the post or the leading edge of a base.

-

- Vertical clearance under a protruding object must be at least 80 inches (2.03 m) above the finished floor. For example, exit signs in a hallway.

-

- Barriers that are detectable by a cane are required where vertical clearance is < 80 inches (2.03m).

The pictures below show sprinkler standpipes in an egress stairwell, where it is clear that a person using a cane for guidance along the stairwell landing could have a serious problem or fall down a flight of stairs.

| Figure 4 Standpipes as protruding objects in stairwells, courtesy of Gene Boecker |

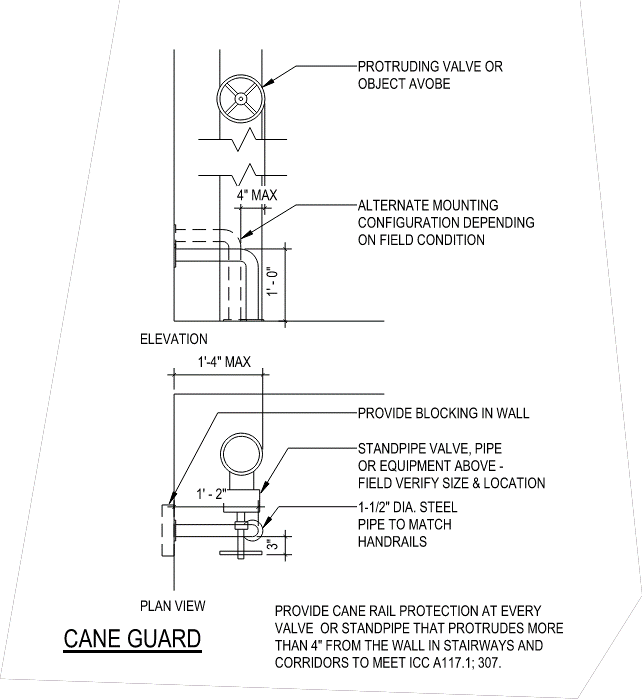

Hose reels and fire department connections in stairwells without appropriate barriers violate protruding objects regulations. Following the guidelines, barriers should be surrounding these life safety features in order for them to be truly life-safe for all persons utilizing the stairwell in question. It is our responsibility to make sure that when we have sprinkler standpipes, hose reels, or fire department connections in stairwells that all of the regulations are met. Appropriate barriers signal to people with visual differences that a protruding object is present must be specified in plans and installed to standard. These oversights, at best, delay building openings. The oversight could land the owner, designer, installer, and the companies they represent in legal jeopardy. The worst of all outcomes would be a person hurt due to the oversight. Life safety features and regulations are intended to protect the lives and bodies of ALL occupants. When accessibility requirements are neglected, human beings are neglected. The following figure shows correct specifications for cane rails or guards around a fire department connection that can be a protruding object:

Conclusion

It is important for us all to remember that, if we are lucky to live long enough, at some point in our lives, we and our loved ones will all be disabled. Whether a disability is permanent or temporary, accessibility is for everyone.